I come from a big Turkmen family, and I am the youngest son, the 8th. When I was 4 months old, my father died. My mother was a schoolteacher in Ashkhabad, and it was very hard on her. She sent me to leave with my grandmother where I stayed until my 7th schoolyear.

I finished my freshman year of high school in the capital, then spent 2 years in a specialization school, and later on went to serve in the army. I reached the rank of a sergeant, made some friends. In 2006, I traveled with them to Turkey to earn some money. You know our visa travel regulations with Russia: everyone goes to Turkey. There, I was a salesman, earned well and was even able to help my mother. But two years later I missed the document renewal deadline, and subsequently was deported.

It was then when I decided to go to Russia. I managed to find company that got me a student visa for a $1000 fee. There was no other way to get there. My brothers helped me collect the needed sum, as they knew I didn’t like my life in our homeland. The amount of money was exorbitant for my family. If in Moscow I make $500 as a loader, in Turkmenistan, one fifth of my salary is considered a good income. You see the difference, don’t you?

In 2010, I came to Russia and enrolled in the specialization school again. Afterwards, I began my studies in a tourism faculty at the university. To pay for my studies, I worked all kinds of jobs: loader, cook, waiter…

In 2014, I discovered my HIV-status. I had to renew my health permit which included an HIV test, and it came positive. At first, I did not understand the gravity of what happened: I did not get my health permit, not such a big deal. However, not having the permit caused me to lose my job and get deprived even of the last salary. I started a cleaner job at a night club, working without a contract but at least getting 1500 to 2000 rubles in cash every day.

As some time passed, my health started to worsen. I didn’t give much thought to it – I was sure it was only because of excessive work and poor diet. Later on, I began experiencing dizziness and fainting.

One day, on my way home from a 24-hour shift, I was robbed of my bag containing money and all my documents. The police wasn’t able to retrieve the lost belongings, so I had to return to my home country to get a new passport. It is not an easy process in Turkmenistan, it takes time. When I came back to Russia, my mates had already finished their studies, while I had to go to work. Thus, I never got to finish the university.

The last visa granted to me was a tourist one. It expired in a month. I could not find a legal job and change my status for a work permit, so I’ve been staying in Moscow undocumented since 2017. With HIV, I can live in Moscow, but not in Turkmenistan. This fact became clear to me when I visited home. I went to an AIDS center there and received a paper certifying absolute health. In Turkmenistan, the mere existence of HIV-infected is being denied. People keep dying, but the truth about it is kept hidden behind the curtains.

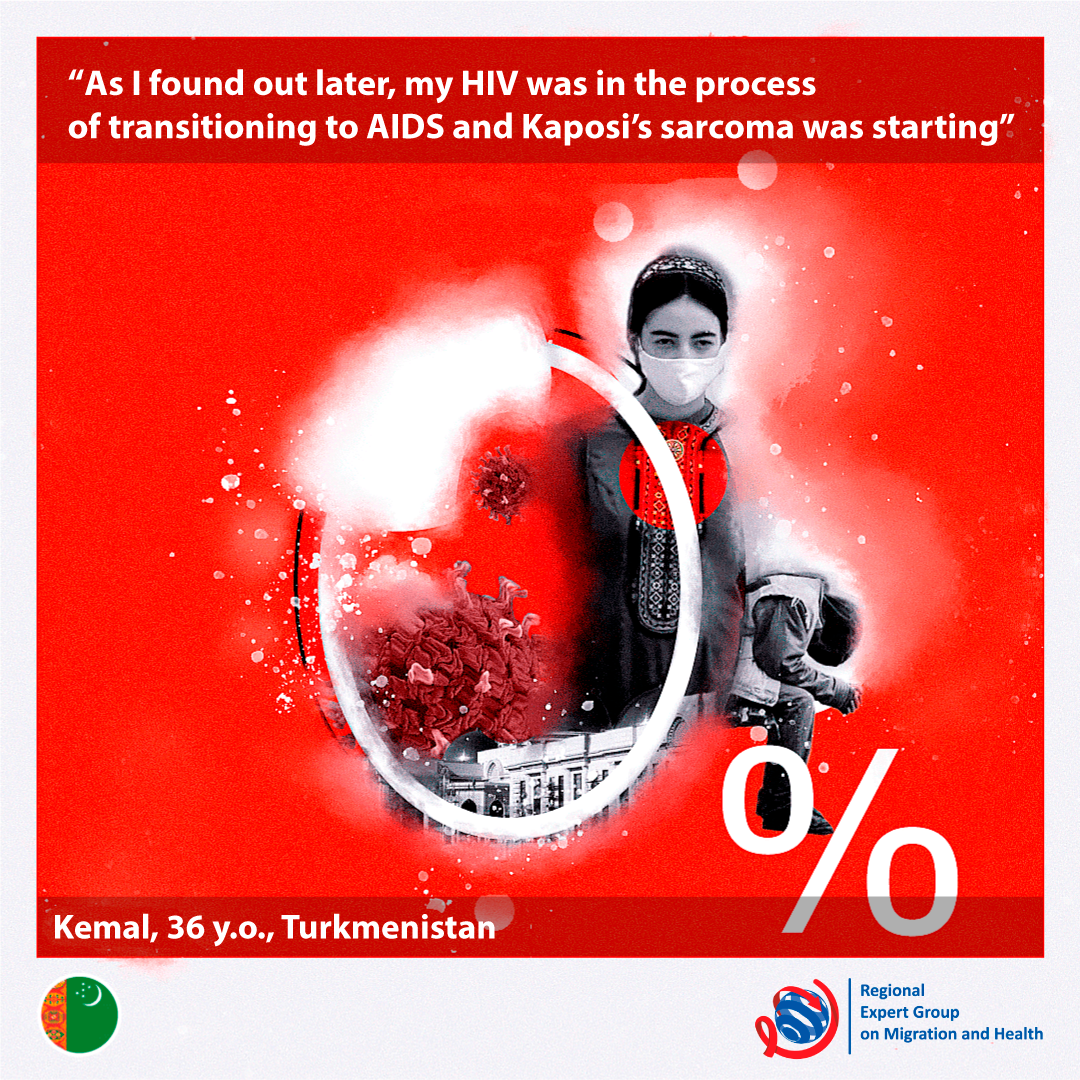

At some point in Moscow, I got very sick, as I had not been taking the therapy since 2014. As I found out later, my HIV was in the process of transitioning to AIDS and Kaposi’s sarcoma was starting. I went to a polyclinic and by pure coincidence met a doctor who saved my life. She was also from Ashkhabad; she immediately knew what was going on with me, called an ambulance, and I was hospitalized. She helped me get in touch with “Shagi” foundation which aided me with the treatment. I am alive now thanks to their support. Even though I am a mere stranger to these people, they still support me immensely. I would have never thought there were people like them left in Russia.

Now, I take jobs where no health permit or contract are needed. I take medications every day. It costs 10 000 rubles per month – a significant amount for an undocumented migrant.

I often think about Turkmenistan. There are many people like me there. They suffer and die. Nobody is there to help them. How can I be of any service to them? No one will hear me there, and if I start active engagement, I will surely disappear the next day. Such people often disappear there.

I know that my only option is to live in Russia. Here, I started to place a much higher value on life. Sometimes, of course, I get overwhelmed by thinking that am not the same as people around me. But I still want to live.

Written by Ekaterina Ivashchenko

Pictures by Aleksandr Nosov

To read the story in Russian, please follow: https://migrationhealth.group/kemal-turkmenistan/