The development of the epidemic indicates that migrants are one of the most vulnerable groups un terms of access to health care. In order to find a way to enable foreign citizens to have access to HIV services no matter what country they are in, the country representatives and the partners of the Regional Group on Migrant Health (REG) met in Tbilisi, Georgia, on November 18-19. The representatives of the NGOs and relevant government agencies from Azerbaijan, Armenia, Belarus, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Russia and Uzbekistan also shared their experience in assisting HIV-positive citizens living abroad.

Stigma and discrimination hinder victory over HIV

Elena Vovk, Technical Officer for Public Health Emergencies and Communicable Diseases at ERB WHO opened the event, emphasizing the role of the community in addressing these issues. For example, the organization’s reports show that “if it weren’t for the enthusiastic community members, neither testing nor treatment would be sufficient in the fight against HIV”.

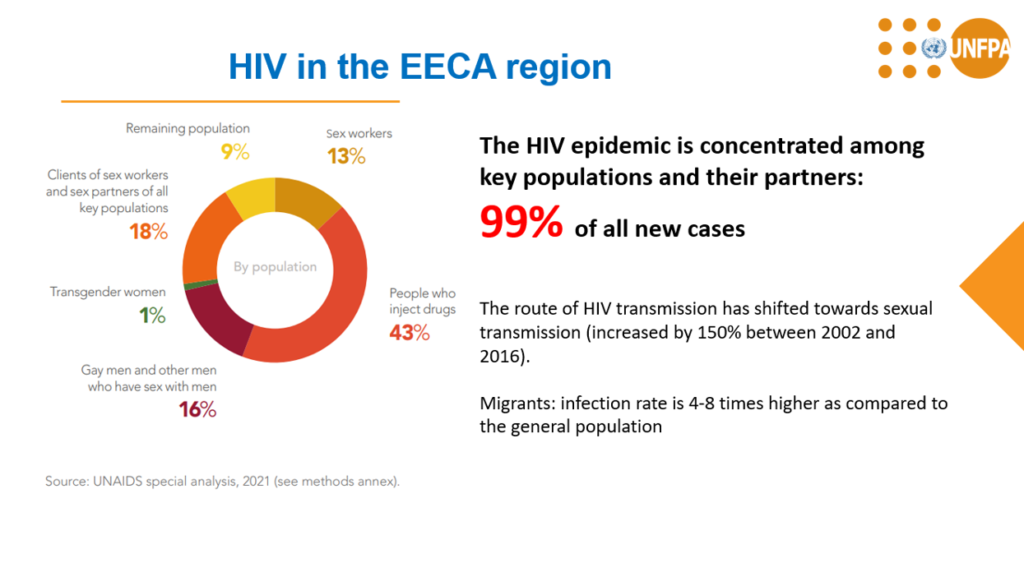

Andrey Poshtaruk, Regional Advisor of the Eastern Europe and Central Asia office of the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) presented an analysis of the epidemiological data. As of the end of 2020, there are 1,600,000 HIV-positive people in the region. Annually this number increases by 140,000, and 35,000 people die of AIDS-related illnesses.

“Eastern Europe and Central Asia (EECA) is the only region in the world where the number of HIV-positive citizens is increasing. At the beginning of 2021, there was a 43% increase in new HIV infections; by way of comparison, the global figure is minus 23%. In other words, the number of infections is falling globally, but in EECA it continues to grow,” said the expert.

The epidemic is concentrated in the key populations (sex workers, IDUs and LGBT people) and their sexual partners, who account for 99% of all new infections. The primary way of transmission has shifted from injecting to sexual transmission, with a 150% increase between 2002 and 2016.

Turning to migration, Poshtaruk noted that mobility and migration significantly affect the likelihood of infection. For this reason, the infection rates among the migrants are four to eight times higher than in the general population.

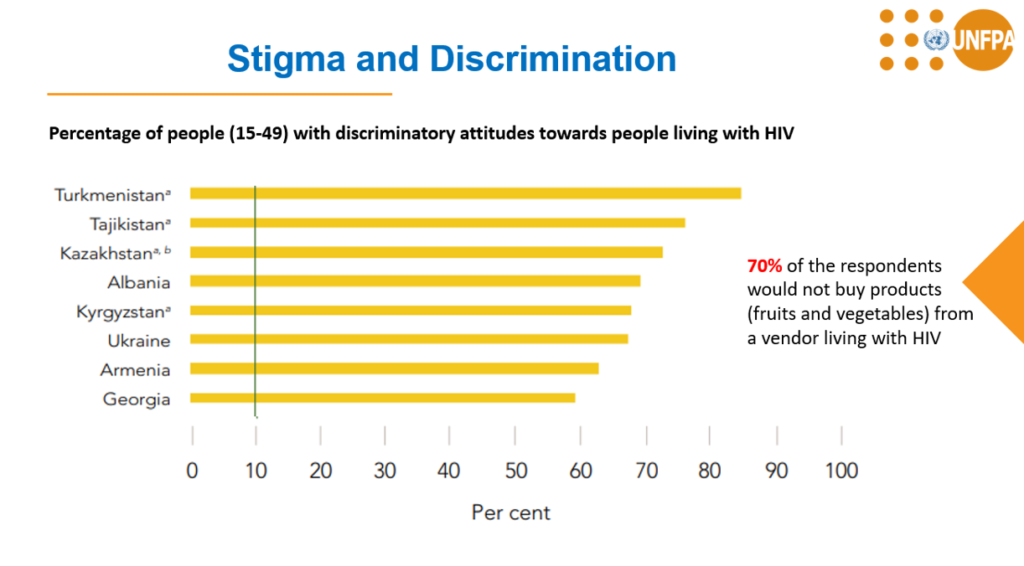

“The main barrier to achieving the goals of combating HIV is stigma and discrimination,” the expert emphasized. – Studies show that 70% of the population in the EECA region are discriminatory against people with HIV.

Punitive legislation

It has been noted that punitive legislation applies to foreigners with HIV in Russia. Not only are they not entitled to tests and ARV therapy, but they are also subject to deportation, even if they officially work and pay their taxes. A foreigner will also be denied a temporary residence permit or a residence permit in Russia if he or she is found to be HIV-positive. Out of the fear of deportation, HIV-positive migrants hide their status and stay in the country illegally.

Anastasia Pokrovskaya, Senior Researcher at the Central Research Institute of Epidemiology of the Russian Federal Consumer Rights Protection and Human Health Control Service, explained how the foreign citizens’ HIV-positive status is reported. A medical institution tests a migrant for HIV (this is mandatory when obtaining a patent for work, as well as when applying for a residence permit or temporary residence permit), all positive results get referred to the reference laboratory, then the data are sent to Rospotrebnadzor, where a decision is automatically issued qualifying the foreigner’s stay in Russia as “undesirable”. After that, the data are transmitted to the Ministry of the Interior and are entered into the database so that the entry to the Russian Federation is banned.

Previously migrants from EAEU states were not required to take an HIV test (except for the requirement to take an HIV test to get a medical certificate), however, starting this year, according to the new amendments to the laws (they will come into force on December 29), all the foreigners who plan to stay in Russia for more than 90 days will have to take an HIV test.

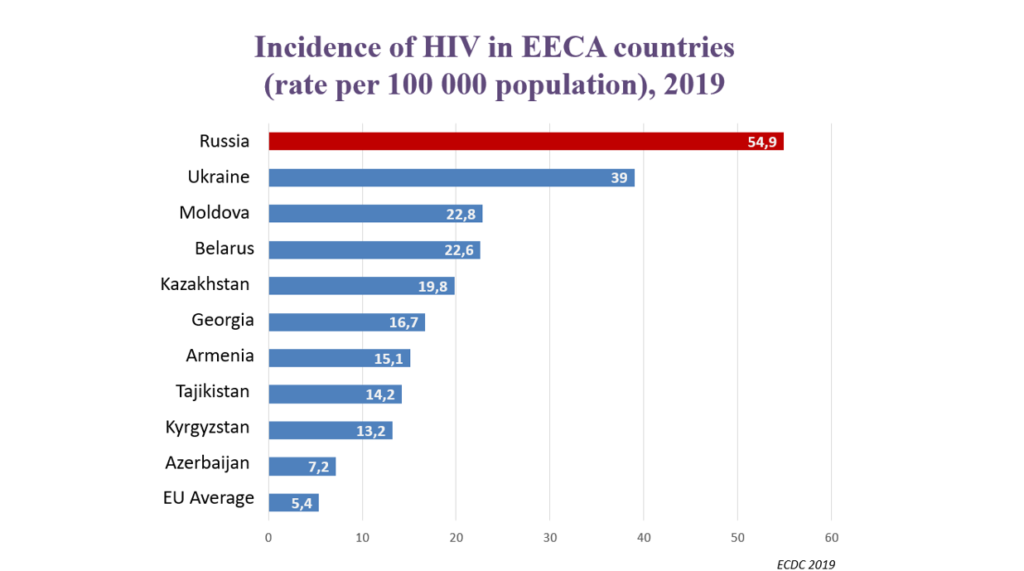

“Russia views HIV-positive foreigners as a threat to Russians; this is justified by the fact that these citizens are allegedly epidemiologically dangerous,” Pokrovskaya notes. – But we know that “danger” depends on many factors and can be prevented, including by ARV therapy. Another question is who is more dangerous: the Russian citizens for a foreigner or the other way round, because the number of new HIV infections in Russia is higher than in EECA countries.

The expert cited some data showing that in Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, HIV prevalence is higher among people who have returned from migration than in the general population. This fact makes it impossible to rule out that the infection could be contracted in Russia, where more than one million citizens live with HIV and its prevalence is increasing annually. As to foreigners, according to Rospotrebnadzor data, only 38,482 people have been diagnosed with HIV in all years of observation (since 1985).

HIV-positive migrants – who are they?

Daniel Kashnitsky, coordinator for REC’s cooperation with the academic community, outlines the main groups of migrants with HIV. First come those who were aware of their HIV-positive status, were registered at the AIDS Center in their country and did not apply for a patent when they came to Russia, so they were not subjected to surveillance, but were able to receive ARV treatment remotely.

The second category are those who are tested in Russia when they apply for a patent or for their temporary residence permit/VNP and are immediately listed as the persons whose stay the Russian authorities deem undesirable. They can stay in Russia if they have close relatives, but nevertheless this does not enable them to be treated in Russia.

The third group are the migrants, whose HIV status is detected anonymously on by the NGOs. They cannot extend their legal stay in the country, but they are aware of their status and take the appropriate measures.

“By last year about 40 thousand foreigners with HIV were cumulatively identified in Russia, but we do not know how many of them have left Russia and how many have stayed. The authorities’ expectation that migrants with HIV will leave Russia on their own never works. Not because migrants are irresponsible, but because these people incur huge debts to come to Russia; they are forced to work here because they have no other source of income at home,” the expert explained, adding that the whole world has long advanced in HIV prevention issues and does not restrict people with HIV in any way, and only the repressive laws of Russia leave migrants back in 1995, when HIV was perceived as a deadly disease.

Difficulties in getting ARV therapy

Sergey Uchayev, chairman of the Uzbek NGO Ishonch va Hayot, confirmed that HIV-positive migrants do not leave Russia, so they try to get their treatment from their AIDS centers in different ways. Read more in the article “Between Two Fires. The Story of an HIV-positive Woman Who Lived in Russia and Uzbekistan”.

“The mechanisms to transfer drugs to Russia are not always effective and one has to disclose his status and get registered with the AIDS center, which people with HIV do not always agree to. Also, people have to spend extra money for this – pay for shipping or courier services. These factors reduce their treatment adherence and increases the risk of a deterioration of their health. Illegal migrants, who have been banned from entering the country, cannot register remotely at the native AIDS center and do not get into the health care system of Russia, so they return in the terminal stages”, – Uchayev said.

The expert underlined that in the absence of targeted programs to support migrants with HIV, people solve their problems themselves or with the help of NGOs. Uchayev shared a story of a migrant woman who could not return to Uzbekistan because of the pandemic and found activists delivering ARV treatment in Russia through instant messengers.

Asmik Harutyunyan, Program Manager at the Armenian Ministry of Health, confirmed that the main problem of migrants with HIV is fact that they cannot continue their treatment legally without fear of being deported.

She noted that because of this, HIV-positive migrants and people with tuberculosis often return home in the terminal stages of the disease.

“It is important that the host country realize that in such a case, these people are a danger to it as well. It is extremely important for the migrants to be able to disclose their status and to receive treatment. Especially since most people get infected with HIV abroad and not in their home country,” Harutyunyan noted.

The representative of the Ministry of Health noted that Armenia is ready to provide the assistance as planned and to transfer the medications to the country of employment if they ensure the monitoring of the treatment.

In the meantime, a temporary solution to the problem is to cooperate with NGOs and to deliver the medications to the migrants’ countries of employment. In 2020 there were 21 deliveries and 300 Armenian migrants in Russia received ARV treatment. Last year Kyrgyzstan gave 500 HIV-positive migrants ARV therapy through their relatives.

All these figures confirm the fact, repeatedly voiced by experts and employees of specialized NGOs, that the deportation rule does not work, and foreigners remain in Russia.

Experts from Tajikistan expressed confidence that the abolition of deportation would be fundamental to maintaining labor migrants. In the meantime, the AIDS Center provides treatment for six months or more to its citizens who are in migration.

They noted that the local AIDS Center is ready to give the therapy to its citizens abroad if the reception, storage and distribution among migrants will be organized in the receiving country.

Kyrgyzstan is also ready to work according to a similar scheme and algorithms for giving the therapy to migrants have been approved. Now the country provides therapy to the citizens going abroad for 12 months. Subject to record keeping, they are also ready to transfer the drugs to specialized organizations in Russia.

Remote Registration

The possibility of developing a system of remote registration of people with HIV in the region was also discussed at the meeting. This would enable them to receive ARV therapy and not to interrupt treatment. That in turn would have a positive impact on the epidemiological situation in the region. Then, in the case of Russia, when applying for a patent or temporary residence permit / temporary residence permit a person will have to take a viral load test, which should be of the appropriate norm. This will be a confirmation for the Russian side that the migrant monitors his health and does not put others at risk.

The representatives of the EECA states agreed that this would make the life of migrants in Russia much easier. For this to happen, migrant-sending countries must negotiate with the relevant agencies of migrant-receiving countries or work within the framework of bilateral agreements, for example within the EAEU.

An example of how such a scheme works is Belarus, with which Russia has a corresponding inter-country agreement, and whose migrants not only do not burden Russia’s health care system, but go to their home country for treatment and medication, knowing that they can safely return.

Ekaterina Ivashchenko