I grew up in a good family in Tashkent. My mother is a laboratory worker, and my father works as a civil servant. Since I was a child, I have always loved attention; I even dreamt of becoming an actor, producing my own movie and starring in it. My parents, however, were not thrilled with this idea – our family is quite religious. Hence, I went on to study in a dental college, and after that, in 2015, I went to Voronezh to continue my education in a medical university.

I was a little afraid to go to Russia as I had heard a lot about Russian nationalism from my relatives. But I have never faced such a problem. Upon coming to Voronezh, I was even a bit disappointed: I expected to see the so-called Cradle of Russian Navy, but what actually unfolded before my eyes was a seaweed-smelling reservoir and grey five-storey apartment blocks. There have been skyscrapers in Tashkent since long ago!

For a while, my parents were supporting me, but then I managed to find a job. First as a waiter, and later as a cook and cashier: I prepare and sell pancakes with fillings. I love Russian cuisine, I adored jellied meat as a kid. It has always seemed to me that I had some Russian traits in me. I even enjoyed Russian music more than Uzbek one.

I found out about my HIV status in January. There was an abscess on my leg which did not go away, so I went to get my blood tested for a variety of causes, including for HIV. But the thought never crossed my mind that I could be infected – I’m the one who has been studying medicine for seven years, who rushes to the library after classes, who never drinks or smokes. I was shocked, I could not believe my diagnosis. I developed such severe depression that I even had occasional suicidal thoughts.

Doctors referred me to the AIDS center. At the time, I wasn’t aware of the fact that foreigners with HIV were being deported. I trusted the doctors who convinced me that everyone could receive treatment there, even a migrant. So, I brought my documents, got registered and then was informed that migrants with HIV were to be deported. Not only did they fail to help, but they made my matters worse by adding me to the deportation list. I was at a dead end. Finally, I was advised to refer to an NGO that helps foreigners with HIV in Russia, and a virologist there commenced with my treatment.

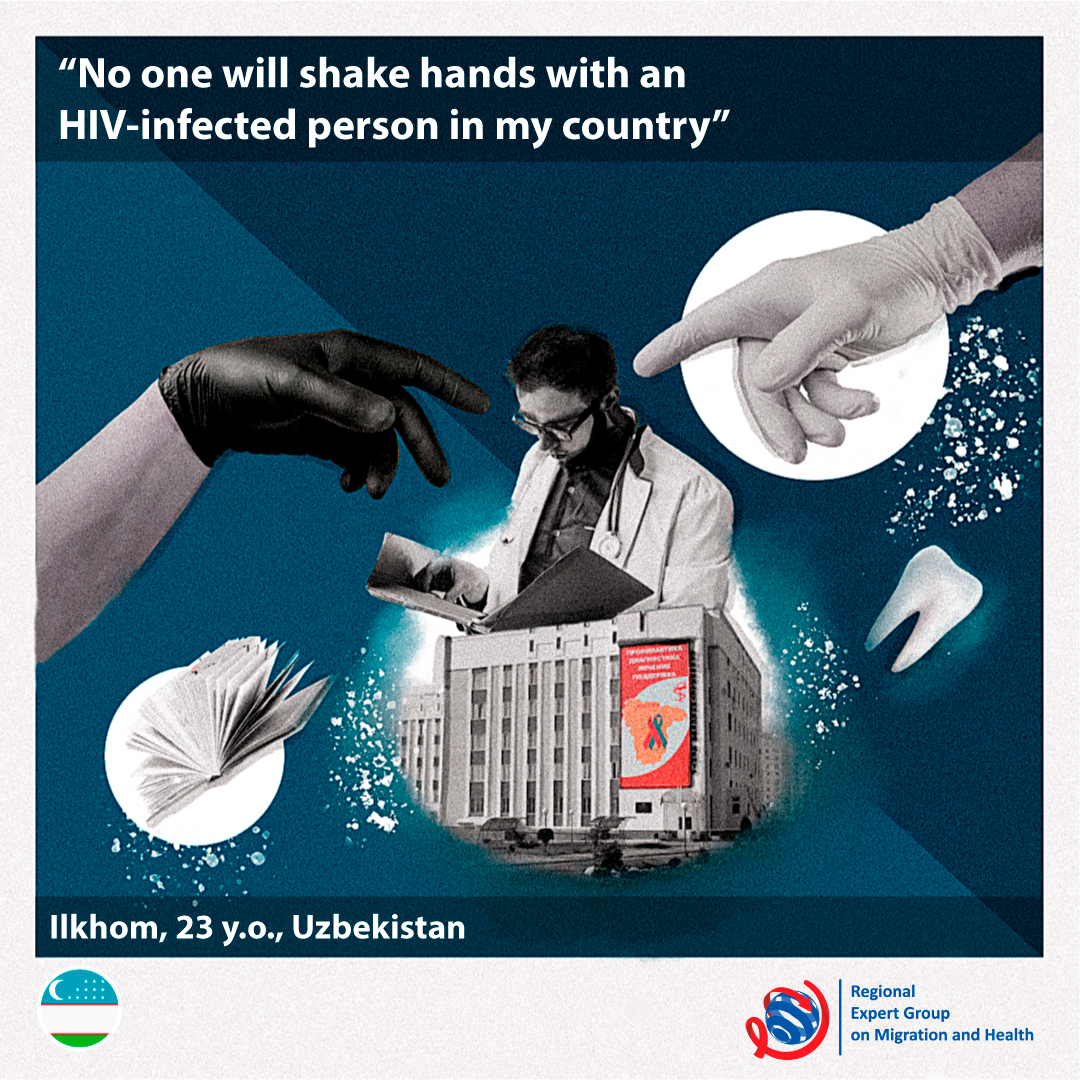

The main issue for me is the attitude towards HIV in my home country; there are too many religious and ethnic barriers there. No one will shake hands with an HIV-infected person in Uzbekistan. It is a shame that even medical professors were misinforming about the HIV-infected individuals: that they have abscesses, facial changes, they lose hair. I don’t understand why they have to repel and scare people so much, but these are the stereotypes that still exist.

What are my plans? Firstly, I am determined to finalize my studies. This is the last year. Then I’ll go back to my country to be able to receive therapy for free. I want to work in accordance with my medical specialty. If I’m not able to return to Russia I will travel the world, like I used to dream when I was little.

No, I won’t disclose anything to my parents. At their age it is already impossible to change the way one views the world. And why should I make them worried? Let them look at me and see Ilkhom, their dear boy.

Written by Ekaterina Ivashchenko

Pictures by Aleksandr Nosov

To read the story in Russian, please follow https://migrationhealth.group/ilhom-uzbekistan/