I was born in the south of Kyrgyzstan, in the oil field workers’ town of Kochkor-Ata, we have quite a large oil field there. My mother raised me and my two sisters; my father passed away when I was five.

After school, I went to Bishkek and enrolled in the Faculty of International Relations at the Kyrgyz National University, but I did not graduate; I took a sabbatical leave in my fourth year. After the death of my grandparents, who were helping us, my mother could not cope on her own, so in 2012 I went to Sakhalin in Russia to earn some money.

There I did flat renovation work. My first salary was 41,000 roubles, or 60,000 soms. By comparison, my mother only got 15,000 soms. I sent most of the money to her.

In 2017, I returned to my home country, I had kidney problems and I was being treated for it. I wanted to stay, but there was no job, so at the end of 2017 I left for Moscow. A construction firm was going to send us to the Sabetta shift camp in the Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous District. Everyone who goes to work there is sent for a compulsory medical examination. I did not pass it due to suspected tuberculosis in the upper lobe of my left lung and I was sent back to Moscow. There I repeated the examination but it showed that there was nothing wrong with me. I ended up staying in Moscow, also working as a construction worker.

In 2019, I returned to my home country and got a job in an oil and gas company. During the 2020 quarantine I felt weak, then started coughing and thought I had COVID. Doctors didn’t understand what was wrong with me, so I went to a private clinic. The X-ray showed TB. The stage was already “good”, as it became known later, drug-resistant.

I planned to get married in the autumn but ended up in hospital. I had to break up with my girlfriend. I didn’t tell her that I had TB, I didn’t know how she would react, so we just broke up.

I was admitted to the hospital, where I am still staying. In principle, it’s OK here, the treatment is free, the doctors are polite, the food is five points out of ten. I’ve lost 13 kilos, but I’ve already gained seven. What is really hard is that TB drugs have serious side effects, which add to the depression from being in hospital for a long time. Now I take 14 pills a day along with vitamins. But my progress is good, and I hope to move to outpatient treatment soon.

In the last two months, the open form on TB has changed to a closed form, and I am now regularly visited by relatives, friends and colleagues. The firm pays my sick leave. Even a doctor from our organisation came here to check on me and talk to the doctors.

I would like to mention that a lot of young people are being treated at the hospital, and many of them have returned from Moscow with tuberculosis. There is a big problem – our guys, not being fully cured, go back to Russia to earn money. And there is a lot of work and poor living conditions there. It’s very dangerous for a person with an untreated TB. All this should be explained to people.

It’s hard to think about it, but I realise that I will have to keep a close eye on my health for another five years after I finish my treatment. You cannot lift weights, which means I won’t be able to work everywhere. There are girls here who are advised to plan pregnancy 2-3 years after treatment at the earliest. That’s how tuberculosis pulls you back.

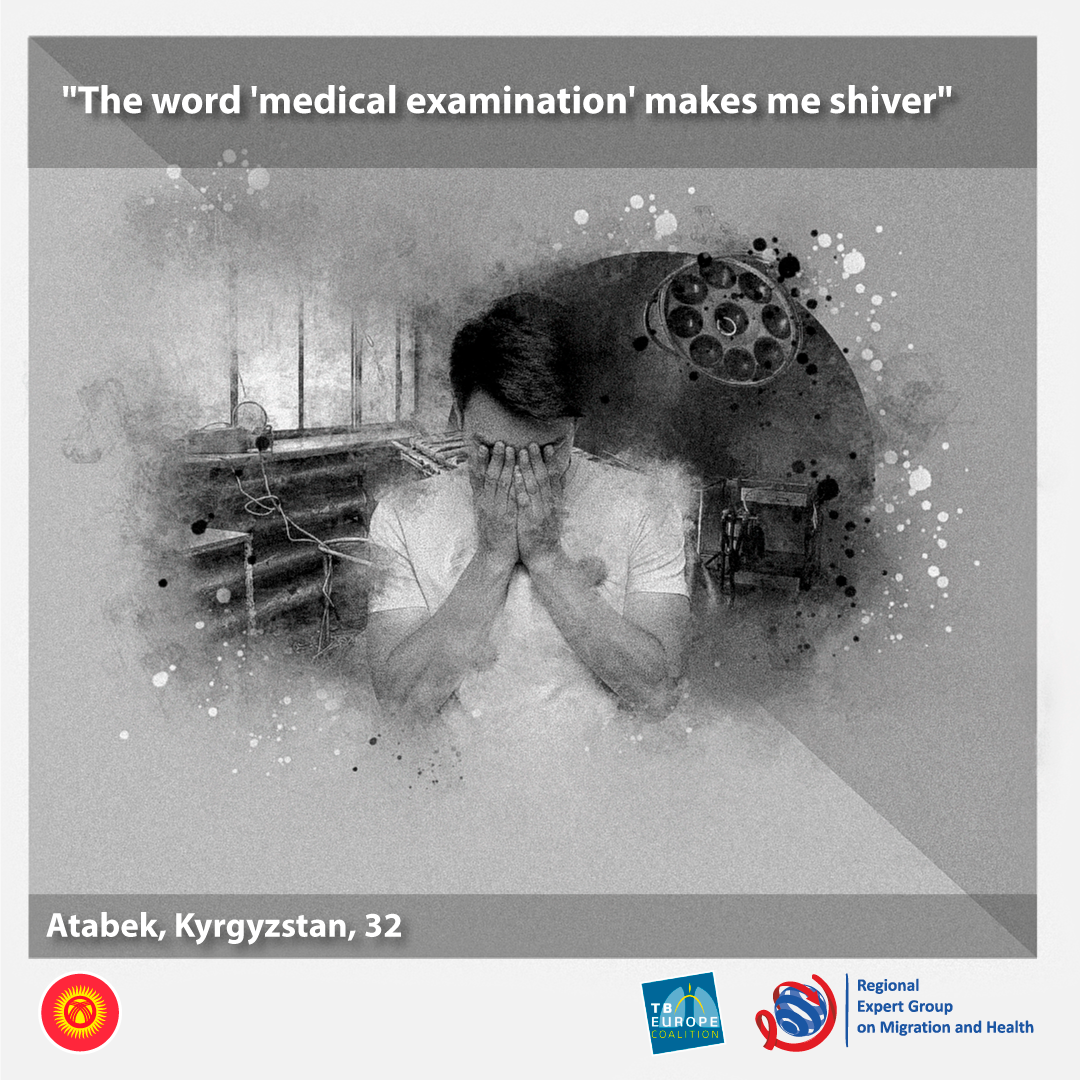

The biggest problem is that even after being cured, we can’t go abroad to work: the remaining changes in the lungs are visible on the X-rays, and they refuse to hire us. I know a person, who recovered from tuberculosis and was called to work in Poland. He had a medical check-up there and the X-ray revealed lung changes and they sent him back. It’s a terrible story. Now the word ‘medical examination’ makes me shiver.

Recorded by Ekaterina Ivashchenko

Illustrations by Alexander Nosov