I am from Severodonetsk – this town is known for its nitrogen chemical plant. My parents worked there. As for me, I decided to follow my own path and after graduating from school I studied to be a plasterer. It was really interesting for me, but I never wanted to be a pilot or an astronaut.

Later I got a job, but then I found myself in a bad situation – exercising self-defence during a fight. So, when I was 21, I was put behind the bars for 8 years.

It was very hard for me in prison. However, I worked and followed the rules, so I was released two years early. We did not receive money for our work there, but it helped me to avoid degradation. Besides, those who worked could live in better conditions and send presents to their family for free. We had an assembly line producing chess sets, icons, bread baskets, kitchen boards and other similar things. My mother loved my presents, her house is full of them.

After my release, I got my LPR documents (edit. – Luhansk People’s Republic is an unrecognized republic on the territory of Ukraine; according to the Order of the RF President, the Russian Federation recognizes the documents issued to people in the Luhansk region of Ukraine) and in early 2018 I came to Moscow to join my mother, who had been living there for several years.

In April, I was admitted to a hospital as my immune status fell down really low. I have HIV and the doctors could not understand what the reason was for my low immune status, but when they did a gastroscopy, they told my mother that it was over… that I would die soon. I had abdominal tuberculosis.

Not a single hospital agreed to treat me. Vladimir Mayanovskiy (edit. – Chair of the Coordination Council of the All-Russian Union of People Living with HIV) helped me; he found a hospital, where I had two surgeries. Because of my low immune status, the sutures did not hold. Then my duodenal ulcer started bleeding because of the treatment with heavy TB medicines. In eighteen months, I had five surgeries, every day I had 12-15 droppers, with the dropper sets looking like decorated New Year trees. For a while, I could not even walk.

By summer 2020, I felt better and was switched to outpatient treatment. For three more years, they will keep me registered with the local TB treatment clinic for follow-up and I will have to do my X-rays and tests regularly.

I received all my treatment free of charge and I am very grateful to my numerous doctors. Where did I get it? I am sure it was not in prison as it was all fine there. I think it happened back when I worked in Moscow at a metal site. There were different people coming here, maybe one of them brought me this plague.

Tuberculosis leaves certain traces on your life. I cannot lift heavy objects. It is better for me to keep away from damp places and not to overtire myself. After tuberculosis, every person has to individually decide what job to choose and how to build their further life.

Besides, I want to say that I spent part of my treatment in a TB treatment centre, in a department for people living with HIV. Only 10-15% of people there really wanted to cure their disease. Others not only kept drinking and smoking, but even took drugs. There were people who did not leave this centre for 10 years, that’s what is scary. During the whole time I received treatment there – for over a year on and off – out of a hundred people there only a few who were making efforts to get cured and never come back.

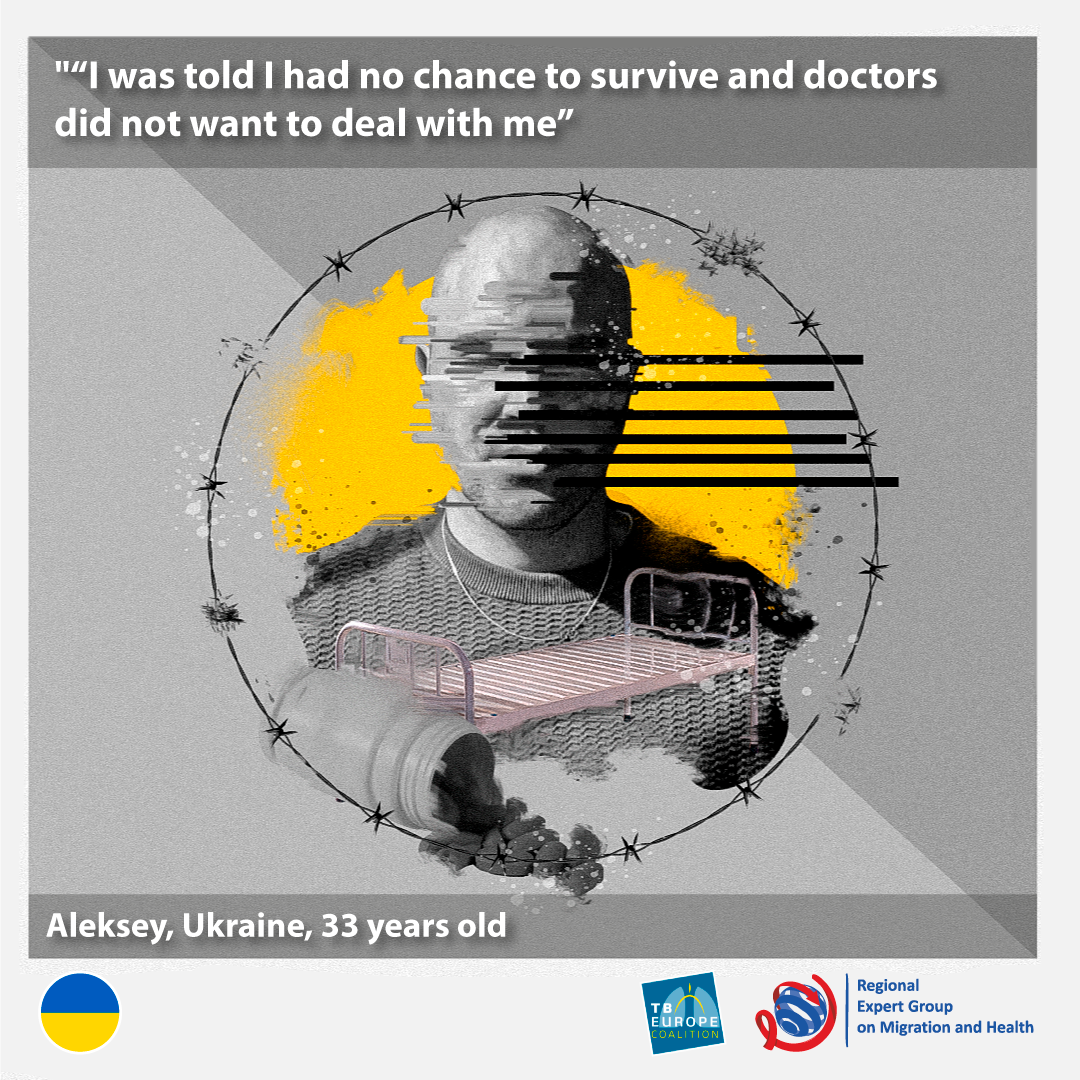

I was told I had no chance to survive and doctors did not want to deal with me, so I am “lucky” rather than “happy.”

By the way, I am not afraid that someone would learn about my HIV status or tuberculosis. Many people know about it and it does not push them away. Nobody ever told me “don’t take my mug.” People look not at your status but at what kind of man you are.

I plan to have a family, but before I need to get more stable financially. Now people live normal lives with HIV and have children. We have groups in messengers, where we talk and support each other. If someone starts feeling depressed, we do what we can to help. People there know each other well; they get married and have children. There are many happy stories.

Written by Ekaterina Ivashchenko

Illustrations by Aleksandr Nosov

Comment by Daniel Kashnitsky, REG expert, Junior Researcher at the Higher School of Economics, Moscow:

“Usually, foreigners, who get sick with tuberculosis in Russia, get treatment within emergency care for the first two weeks – up to the moment, when they become smear-negative, which means that they are not a danger to people around them and cannot transmit the infection anymore. Then they are told that to continue their treatment they need to go back to “their home country.” Some patients, who are really lucky, manage to complete their treatment without leaving Russia. It is possible in some cases – if the administration of the health facility finds a way to register the foreigner under another category such as a homeless person or in some other way. This is what happened in the case of Aleksey. To eliminate the risks of tuberculosis treatment interruption and development of severe complications, it is crucial to create the conditions for migrants to complete their tuberculosis treatment where they start it.”