I was born in Vinnitsa, Ukraine, in a common soviet family: father a mine worker, mother a cook in a clothing factory canteen. After they divorced, my brother, sister, and I ended up in an orphanage, but later on, my father took me to Vorkuta where he was living at the time.

After finishing school, I had to return to Vinnitsa to help my mother who had fallen ill. In Ukraine, I graduated from a technical high school, got married, and gave birth to two kids. However, the marriage didn’t last, and we ended up getting a divorce. Consequently, I was left with neither shelter nor a job. I made a decision to start a new life and moved to Russia in 2013, first to Vorkuta, where my father lived, and half a year later to Moscow.

For a while everything had been going well: I got a job as a cook and was staying in a hostel, earning my living. I met a good man and got married for the second time. I was in no rush to apply for a citizenship. In 2016 my husband was killed in an accident.

I decided to apply for Russian citizenship, being a Russian native speaker; my dad helped me to prepare the documents. But a blood test showed HIV infection. I was given a paper ordering to leave Russia, and a lifetime entrance ban. So, in 2019 I had to return to Ukraine.

I had a right to stay in Russia: the deportation law does not affect those whose family members are Russian citizens. I got in touch with the lawyers, we prepared all the necessary documents on time, but the court declared that we are late, and the Rozpotrebnadzor (Federal agency that works to provide oversight and control of wellbeing and consumer rights and protection of the citizens of Russia, including HIV care) ruling was sustained. The stress caused by these news resulted in my father having a heart attack, and he passed away in August 2019. On account of the law on deporting HIV-positive people, I was even deprived of a chance to say goodbye to my father.

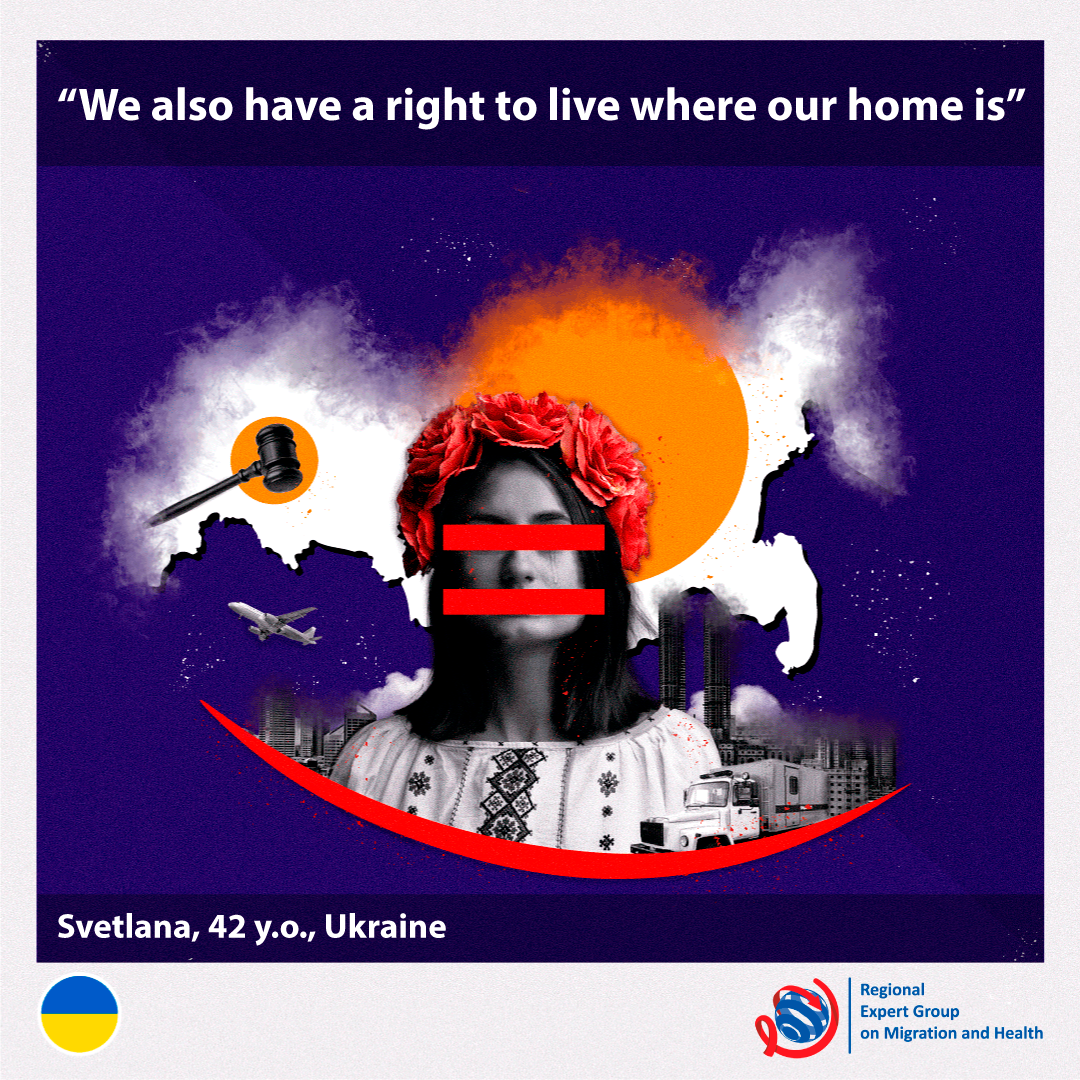

I always considered Russia my motherland. My sister lives there, my father is buried there. I left my significant other, friends, and a job in Moscow. All the things important to my life are in Russia. It is not right to expel a person from the country in a manner like this. People who make decisions should at least ask if a person has parents or kids in Russia. We are no different than others and should be able to live where our home is. I don’t use drugs, don’t smoke; I live a normal life, I work and pay taxes.

Fortunately, my partner is ready to come to Ukraine and marry me; after that we are going to appeal to court once more and try to fight for my right to live in Russia.

Written by Ekaterina Ivashchenko

Pictures by Aleksandr Nosov

To read the story in Russian, please follow: https://migrationhealth.group/svetlana_ukraina/