Oleg was born in Mariupol, Ukraine. He is 55 and he has been living with HIV for 24 years. In the 90s, Oleg started using drugs and got infected with HIV and hepatitis C.

“She looked like Kim Basinger”

In the early 2000s, Oleg headed to Moscow to make some money and got a job at a tire shop. In 2011, he went back to using heroin and stayed in Moscow with no proper legal status – he found a firm, which sold him migration certificates and employment permits.

Soon he met a woman and they moved in together. Oleg wanted to get married and decided to quit drugs, gradually bringing down his dose. “She was blond and had a real, extraordinary beauty,” tells Oleg. “In a way, she looked like Kim Basinger. So, it no surprise that the “shadow” owner of the shop, where she worked, got a crush on her. Later I learned that he was the chief of the local police station. Soon I was arrested at work for possession (editor’s note: of drugs) and sent to Matrosskaya Tishina prison and then to a colony in Ryazan.”

Three years later, after he was released, Oleg went back to Moscow. There was already a military conflict in the east of Ukraine, so Russia could not deport him. Besides, he had nowhere to go. He got a job at a tire shop again. There was a lot of work and it paid well.

However, as Oleg was a Ukrainian citizen and had a criminal record, he came onto the radar of a local chief police officer, who started asking the man to get his car fixed for free. “Soon he was bringing not only his colleagues and bosses, but also a lot of ‘random’ people and I had to spend all my time fixing their cars. Once I got angry and told him what I thought about it. I told him he was going rogue. After that, police came to me and found 150 grams of heroin.”

Oleg spent a year in a pre-trial detention centre, where his tuberculosis started to quickly progress. He was offered treatment for HIV, but they only had two regimens, which made him sick, so he decided to quit the therapy. “My haemoglobin was very low, so they took me to the AIDS centre, where they ran all the tests, they inserted a catheter and were giving me IVs.” Because of Oleg’s health status, his was not arrested and he had to be released, but the prison management put some pressure on doctors and within a week he was taken from the hospital to Matrosskaya Tishina prison.

“This ‘Motorka’ is well-known all over Russia”

The prosecutor was asking to give him 35 years behind the bars, but the judge decided to give him “only” 13. The man was transported to Vladimir, where he spent six months in a TB treatment centre at the colony. “This ‘Motorka’ is well-known all over Russia – it’s a horrible place, worse than an isolation ward. Every day they made me take up to 42 pills – there were two hospital attendants, a cop and a nurse standing over your neck and you had to take them all in – nobody cared if you felt bad or not. They also had this thing there called “full confession” and that’s what they did to me – told me to put my feet at shoulder length with my hands behind my back and were pouring ice-cold water on me for 40 minutes. I got herpes Zoster and my skin was falling off like wet paper.”

However, even in those conditions they were able to put Oleg back on his feet. “I have to say thank you to doctor Krylov, who literally brought me back from the dead.” He was prescribed an ART regimen he was finally able to take.

“At five o’clock in the morning it started snowing and I was standing there barefoot”

In 2019, prison management decided to release Oleg early on the basis of his diagnoses. “I got a second category of disability. To be released, my relatives had to sign a letter confirming that they would meet, support, help and treat me.” Oleg’s relatives did and on May 12, 2020 he was released. When the man left the prison, he did not receive any antiretrovirals or TB drugs. “I could hardly walk, was feverish and did not have any warm clothes – I only had my sweatsuit and my sandals from the prison. I had a hard time getting to Rybinsk and spent a night at the railway station. In the morning, it started snowing and I was standing there barefoot.”

“You can go wherever you want”

Oleg’s relatives bought him some essentials and took him to a TB treatment clinic in Yaroslavl, where he was soon told he had to pay three thousand roubles for every day of his stay. “They said otherwise they would release me. They called police, and police officers said they would use their force. I had no choice, so I packed and left.”

Oleg went to Moscow, but he felt sick in the train. “I have to give credit to the train hostess, who took my blood pressure and temperature. She called medical officers, who were waiting for me at the train station in Moscow.” At the first-aid centre, Oleg was given some blood pressure pills and pain-killers “to go.” “They sent me to Belgorod (editor’s note: a city bordering Ukraine). There was another delegation of doctors waiting for me there, who took me to a checkpoint at the border of the Kharkov region. When they saw my documents, they all started avoiding me.” A border guard guided Oleg to the territory of Ukraine ahead of other people waiting in line and told him: “You can go wherever you want.”

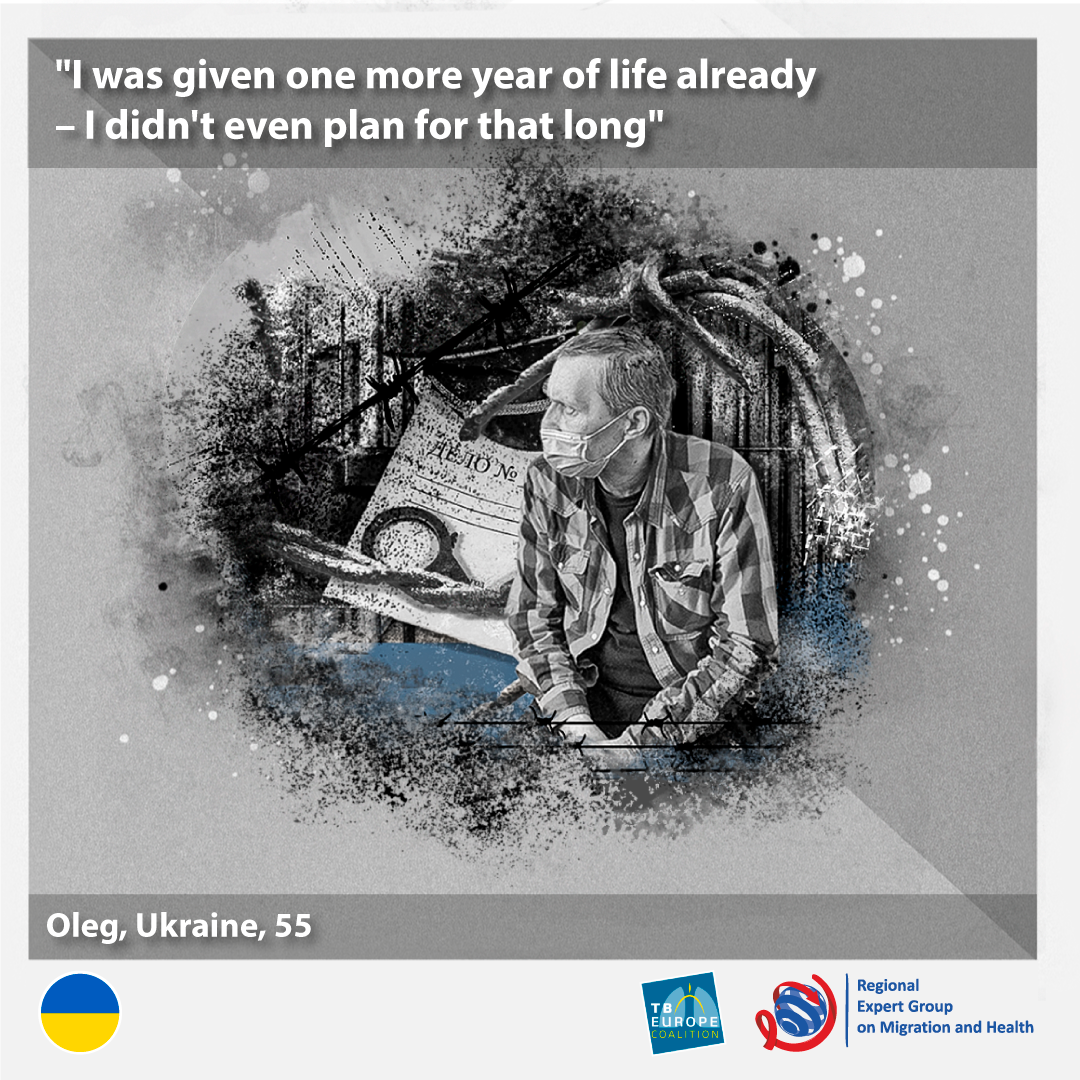

“I was given one more year of life already – I didn’t even plan for that long”

The driver of a truck passing by helped Oleg to get to Kharkov and gave him 100 hryvnias (3 euros). When he got to the city, he felt even worse. “I was asking people where the TB treatment clinic was and was given two addresses, both wrong. Then I just sat on a bench and called an ambulance – that’s how I got to the regional hospital.”

There he met social workers from the Kharkov branch of All-Ukrainian Network of PLWH, who helped him get access to ART and, more importantly, get a disability status according to the Ukrainian laws: “I’m waiting for my disability pension – this month I will get it for the first time.”

Oleg was diagnosed with drug-resistant tuberculosis. Doctors had to change a number of regimens before they could find the right one. “When I came here, I had a viral load of one million six hundred (editor’s note: thousand copies of HIV RNA) and (editor’s note: an immune status of) 40 CD4 cells. Now I have undetectable viral load and my cells went up to 74.” In the regional TB treatment clinic, Oleg also started receiving opioid substitution treatment.

Now Oleg plans to complete his TB treatment and then take care of his hepatitis C – people from the Network of PLWH helped him sign up for the waiting list to receive free hepatitis C treatment from the government. He already has a place to live and a job in Kharkov – he is a watchman in a gated community: “The house needs to be fixed, of course, but at least I’ve got a roof over my head. I thought if God got me out of prison, maybe I will have some more time to live. It is easy to kick the bucket, but it is hard to stay alive. I was given one more year of life already – I didn’t even plan for that long.”

Written by Kristina Rivera

Illustrations by Aleksandr Nosov