I come from a Georgian town of Rustavi where my parents worked at a metallurgic plant famous from the times of USSR. This town was founded by my grandfather. I went to school there. My two brothers went to study in Khimki, Russia, right after having finished high school in our home town. One of my brothers suffered a severe injury there, and became incapacitated. In 1996 I went there to help him, simultaneously working in a store. Several years later my brother died. Later on, my second brother had gone missing, and I took in his little son to raise him.

I was so preoccupied with my brothers’ issues that it slipped my mind completely to update my residence documents timely. Consequently, I found myself undocumented. In Georgia, I automatically received my citizenship at the age of 16, but I still had my old Soviet passport. I did not change it for a Russian passport, and as a Georgian citizen, I overstayed in Russia. I don’t know where to go now to apply for citizenship, how to explain that I am ethnically a Russian, and where to get the needed information. Several years ago, I applied for the homelander resettlement program, but my application was denied.

My HIV status got revealed by pure incident. I knew nothing about it; I thought if you have HIV, you are a living dead. I have completely driven myself into a corner, I even used separate tableware in order not to not infect my child. I did not even understand that it is impossible to infect someone through dishes. I used to isolate everything I owned: towels, bedlinen, etc.

Three years ago, I saw a vehicle of “Shagi” foundation near a subway station. Volunteers were conducting tests there. I took the HIV test once more and got a chance to talk to them. These people became my saviors, they brought me back to life. Frankly speaking, at the time I was already preparing to die. But they laughed kindly at me, explaining that there is still a lot for me to learn about HIV and the modern ways of its treatment. Before that, I knew nothing about my diagnosis, and I was afraid to know. But they explained everything to me in such a comprehensible way that I felt a great deal of relief.

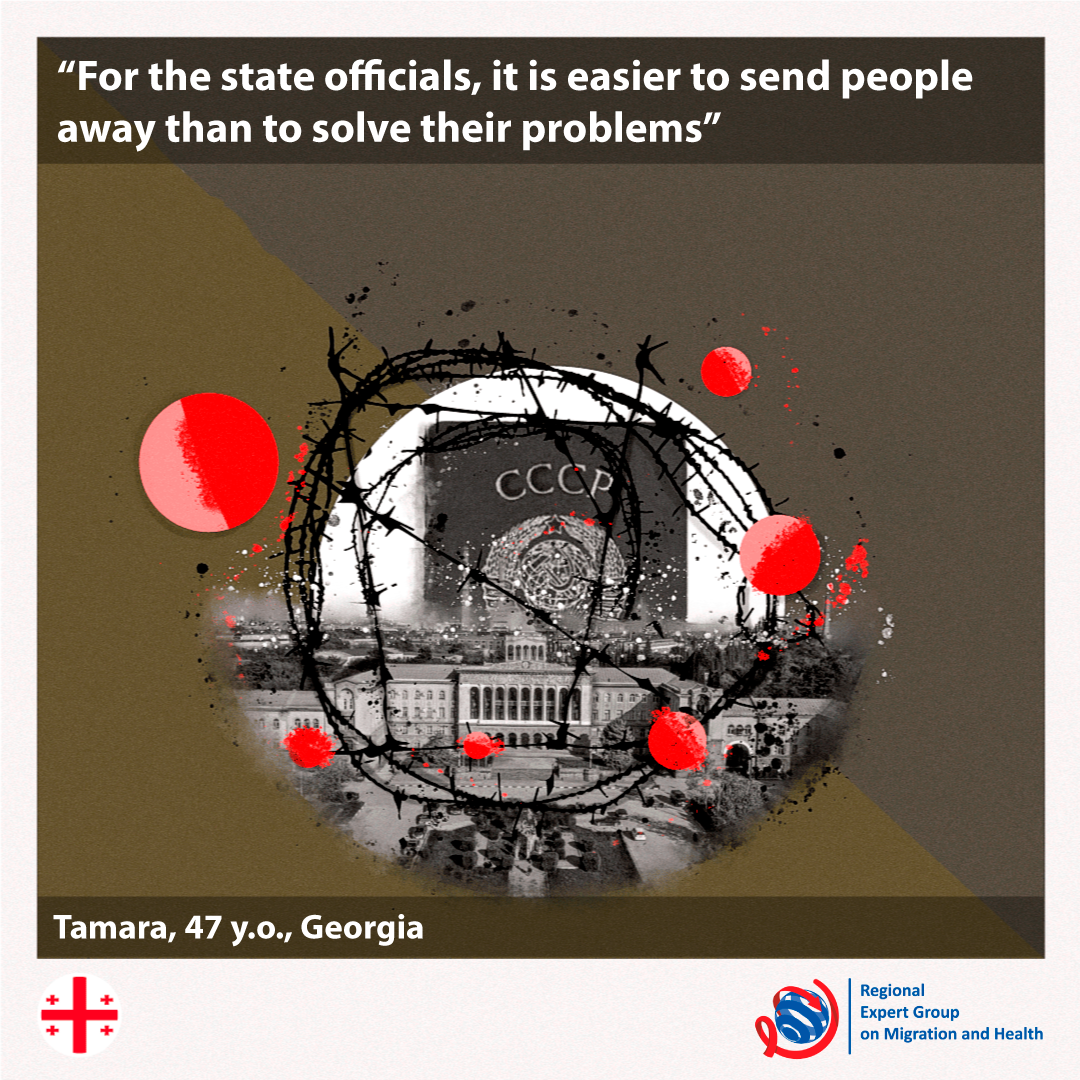

Unfortunately, the Russian officials have a different attitude towards the HIV-infected foreigners. It is easier for them to part company with a person than to solve their problems. Deportation, that’s the end of story. I am even afraid to bring up this topic. We are a caste of people who don’t exist. And there is nothing I can do about it.

Written by Ekaterina Ivashchenko

Pictures by Aleksandr Nosov

To read the story in Russian, please follow: https://migrationhealth.group/tamara-gruzia/